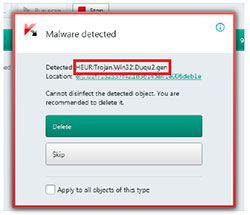

Kaspersky Labs has admitted to falling prey to a new variant of the Duqu Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) which it had previously investigated.

As part of that previous investigation, Kaspersky announced that organisation behind Duqu had gone quiet in 2012 and that the project was presumed ended. Like all good malware and magic tricks, however, it appears that was pure misdirection and Kaspersky has found itself a victim of an updated version of Duqu.

Before going into the details of the attack, it is important to acknowledge the willingness of Kaspersky to be transparent about being a victim. All security companies, researchers and even security magazines accept that their jobs put them firmly in the firing line.

However, there have been extremely very few incidents where a vendor has openly admitted to be a victim. The fact that Kaspersky has gone public and published all the details of the attack is important. It outlines the need for cybersecurity to be a continual process, something that many CISOs still struggle with.

IBM, HP, the RAND Corporation and Juniper Network have all published data recently showing that CISOs believe they’ve invested enough in cybersecurity. This attack against Kaspersky shows that such a view is badly misplaced and funding for cybersecurity must be considered part of an ongoing expense.

How did Kaspersky get infected?

This is not an unreasonable question and one covered in detail by Kaspersky in the documents it has provided. It appears that the attack started with a spear-phishing attack against one of Kaspersky’s smaller APAC offices.

It is believed that it took advantage of a zero day exploit (CVE-2014-4148) to jump from a Microsoft Word document into the Kernel of the Windows operating system and infect the machine. Despite the exploit being patched as soon as Microsoft released an update, it appears that the infection was not detectable.

The sophistication of Duqu 2.0 is remarkable. Rather than run riot inside Kaspersky Labs the attackers are believed to have carefully mapped the corporate network topology and then moved itself to other machines using another zero-day exploit (CVE-2014-6324).

By now, the attackers had administrator privileges on the machines they had infected. This allowed them to create Microsoft Windows Installer Packages (MSI), deploy them to other machines and execute them using a remote service call. According to the documents from Kaspersky, this is the same behaviour spotted by Symantec in the original 2011 Duqu attack.

Another zero-day exploit used by the hackers (CVE-2015-2360) was detected by Kaspersky themselves as a result of this attack. The details were passed to Microsoft who on the 9th June issued a patch.

What is notable here is the effective use of zero day exploits that even when patched, seemed to go undetected. Kaspersky admits that the first they knew of the attack was when it detected a cyber-intrusion in early spring 2015. Even then, finding the evidence was extremely difficult because the attackers cleaned up after themselves making it extremely hard to find the evidence of the attack.

What were the attackers after?

According to the Kaspersky press release : “Kaspersky Lab strongly believes the primary goal of the attack was to acquire information on the company’s newest technologies. The attackers were especially interested in the details of product innovations including Kaspersky Lab’s Secure Operating System, Kaspersky Fraud Prevention, Kaspersky Security Network and Anti-APT solutions and services. Non-R&D departments (sales, marketing, communications, legal) were out of attackers’ interests.”

Note that this statement stops short of mentioning source code. If the attackers have managed to get copies of source code then the severity of this attack becomes severe. Many of the zero-day exploits that have occurred around Adobe products in the last two years are believed to be as a result of the massive breach it suffered where code for multiple products, especially Adobe Flash, were stolen.

Who were the targets?

While Kaspersky Labs have admitted to be a target and a victim, there has been silence from other security vendors as to whether they have found traces of an attack or infection on their systems. In its documents, Kaspersky has said that the primary focus appears to have been to spy on the P4+1 talks over the Iranian nuclear programme.

Given this and the historical links to Stuxnet, a lot of security commentators believe that the most likely source of this Duqu is the Israeli security services. They are known to have collaborated with the US to help develop Stuxnet and have already been shown to have spied on the talks.

Kaspersky has been circumspect on its attribution for the attack. It has noted several attempts to misdirect researchers in the code saying: “..such false flags are relatively easy to spot, especially when the attacker is extremely careful not to make any other mistakes.” It also points out that the work week, based on code compilation data seems to indicator a Sunday to Thursday work week. This information also throws the spotlight firmly on the Middle East without identifying any one country in particular.

Kaspersky has also said that the group behind Duqu 2.0 also launched an attack on the 70th anniversary event of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. While some security experts in closed Internet groups have been speculating that this might have been misdirection it also opens up the possibility that the attackers could have come from another Middle-East country or even China who were not part of the Iran nuclear talks.

What information is there about the Duqu 2.0 attack?

Kaspersky has published several documents detailing what happened and what it now knows.

- The press release where Kaspersky gives an outline of the attack, its preliminary conclusions and assures customers that Kaspersky products, technologies and services are still safe.

- The Duqu 2.0 Frequently Asked Questions page. This runs to seven pages and gives more detail on the targets of Duqu 2.0, addresses customer concerns about the impact on Kaspersky labs and provides some remedial action customers can take.

- The Duqu 2.0 technical paper which runs to 46 pages. It should be read by every member of corporate security teams. It provides an analysis of Duqu 2.0, the various payloads that have been found, the platform modules it uses and its command and control structure. The report also covers the similarities between the two versions of Duqu.

- An Indicators of Compromise page which is an XML page but where the schema doesn’t seem to be locatable. Hopefully this will be fixed soon.

Kaspersky has also pointed customers to blog posts from competitor Symantec and security research lab CrySyS.

Conclusion

This resurgence of an APT that everyone thought had gone away will make security researchers think more carefully about what they know. A number of companies will now be going back over previous APT’s to see if there is any activity from the groups behind them to indicate that they have become active with new versions.

This attack also throws more attention on the length of time it takes between an exploit being discovered and vendors patching it. While companies are beginning to pay researchers bounty payments for details of exploits, there is evidence that some are willing to sell to the highest bidder which is rarely likely to be the software vendors.

Once Kaspersky has completed its audit and mapped out the entirety of the attack, we may discover yet more secrets of how this attack works. Before then, companies need to begin looking closely at their systems and making sure that their patching is up to date and that they ensure their security sweeps are regular and comprehensive.