Auto hacking is a topic that will always get a place at the various hackers conferences around the world. Despite proven hacks going back several years parts of the auto industry are still in denial about the seriousness and severity of the problem. After several high profile proof of concept hacks last year, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) commissioned a report to see just how serious the problem is.

The report can be downloaded free of charge from the GAO website and backs up what many researchers have been saying. With so much focus on autonomous vehicles any risk of hacking has to be taken seriously. This is not just a report for the global auto industry. It should also interest software companies and those investing in technologies around autonomous vehicles.

Manufacturers underestimating hacker collectives

Right from the start the report pulls no punches. In its findings it opens with:

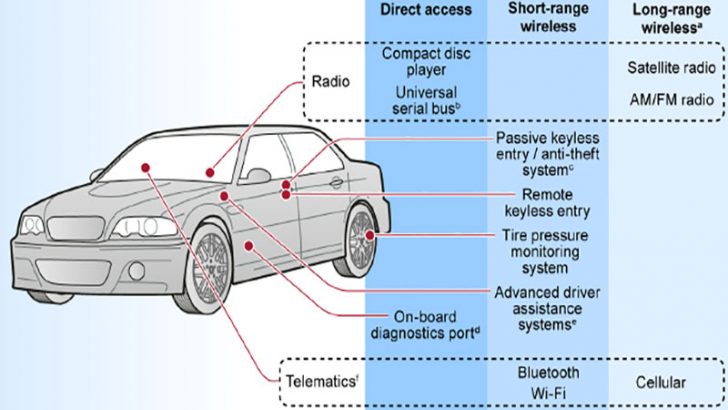

“Modern vehicles contain multiple interfaces—connections between the vehicle and external networks—that leave vehicle systems, including safety-critical systems, such as braking and steering, vulnerable to cyberattacks.”

It highlights how researchers have been able to exploit a range of technologies from physical to wireless access, including Bluetooth, to take control of vehicles.

Interestingly all the stakeholders in the auto industry that contributed to the report said that the mandated on-board diagnostics port was their main security concern. Just two-thirds felt that wireless attacks exploiting cellular would pose the largest threat to passenger safety. This is due to the fact that the auto manufacturers think the time and expertise makes them too difficult.

That response jars with the report which states: “Such attacks could potentially impact a large number of vehicles and allow an attacker to access targeted vehicles from anywhere in the world.” It also demonstrates a complete failure to grasp the speed with which the hacking community is capable of collaborating to develop attacks. As we’ve seen before they are able to bring together greater skills than governments and commercial companies. Dismissing this type of attack in this way appears to be irresponsible.

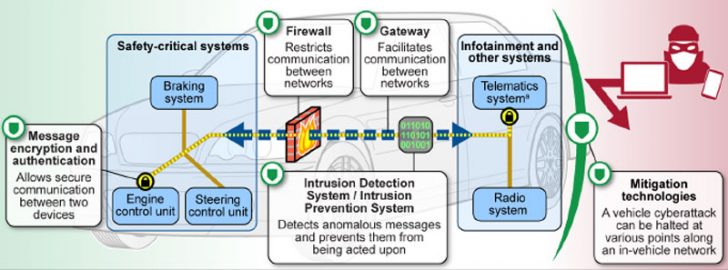

Manufacturers relying on cybersecurity mitigation technologies

In their defence, the auto manufacturers have said that there are several areas in which they can deploy cybersecurity mitigation technologies to protect vehicles. Unfortunately some of these have already been shown to be breachable such as wireless attacks on car pressure sensors allowing control over braking and acceleration.

Two other challenges that auto manufacturers cite are: “the lack of transparency, communication, and collaboration regarding vehicles’ cybersecurity among the various levels of the automotive supply chain and the cost of incorporating cybersecurity protections into vehicles.” These claims have to be looked at in more detail.

The auto industry has one of the highest after market parts ecosystems in the world. It is arguably wider and far more established than the IT industry and many of the interfaces are well documented in maintenance manuals. The EU already requires auto manufacturers to make documentation available to garages and repair shops. Extending this to manufacturers of radio and other third-party components is relatively easy.

A need for standardisation

The biggest issue is the lack of standardisation in the interfaces. This means that third-party component manufacturers currently have to create specific components for different manufacturers. The US is already establishing an Automotive Information Sharing and Analysis Center (ISAC) to collect and analyze intelligence information. That same body will act as a focal point to share threat and vulnerability information between auto manufacturers.

In Europe efforts towards standardisation are unsurprisingly being led by the German auto industry. There is already working going on to extend the ISO 26262 standard and make it applicable to vehicle cybersecurity. The EU Crystal project is also coming to a conclusion and this has looked at a number of use cases for promoting greater standardisation for developing new IT systems. German auto manufacturers established the AUTOSAR partnership over a decade ago. It is now looking at vehicle software and cybersecurity.

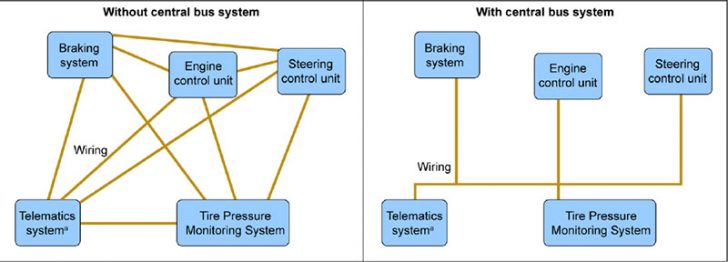

Computerisation at the core of the problem

While computerisation has its benefits it also has drawbacks. In the auto industry manufacturers have simplified their control systems through the use of computer control units. The problem is that the same simplification makes it easier for a hacker to take control. Instead of attacking multiple systems they now require to gain access to just the central bus system. Once they have breached this they can then begin to attack other systems.

It was a the central bus system that allowed hackers who used wireless to attack tyre pressure sensors to then take control of a moving vehicle. Having gained access to the central bus they were able to jump between systems. It is easy to take the IT approach and say that anything coming through the tyre pressure system should not have had the privileges to attack other systems. However from a safety perspective low tyre pressures should be able to apply the brakes to prevent an accident which means better security is required here.

Another downside of technology is lines of code. We consider modern aircraft as being very complex but the report says a different thing. For example there are 1.7 million lines of code in a F-22 fighter aircraft. By comparison the Boeing 787 Dreamliner boast over 6.5 million lines of code that have taken a lot of time to debug. The average luxury car, according to this report, contains over 100 million lines of code.

So what’s the issue with the number of lines per code. According to Steve McConnell in his book Code Complete the average number of code defects per 1,000 lines of code (KLOC) is in the range of 15-50 defects. He also cites Microsoft as achieving a rate of 10-20 defects per KLOC in testing with that dropping to 0.5 defects per KLOC in production. Taking the Microsoft production number that would mean the average luxury car could contain as little as 50,000 defects. The problem is that we don’t know how many there are and how many of these could lead to vulnerabilities.

Over the last two years auto manufacturers have rushed to appear on stage with big IT vendors. Their subject of choice is opening up the car ecosystem by publishing APIs that would make it easier for developers to write applications for vehicles. The more access they provide the more likely it is that any software defects will come back to haunt them. What is needed is for the industry to prove that it is doing a better job of eliminating code defects than any other industry and can be seen as best of breed.

The difference between aircraft and automobiles is the critical safety barrier and liability that manufacturers have to achieve. Auto manufacturers are not regulated anywhere near as strictly nor do they have to prove their software stability to the same degree as the aerospace industry does. Worryingly as we move toward autonomous vehicles there are many in the industry who are warning against introducing software safety standards that are too strict.

A playbook for hackers?

As you read through the report it seems to offer up a wealth of possibilities for anyone interesting in hacking auto systems. While none of the information is likely to be of a huge technical benefit to attackers it does lay bare the confusion and lack of progress across the industry around this topic.

Conclusion

This is a report that needs to be much more widely read than it will inevitably be. Auto manufacturers, anyone who wants to develop software for autonomous vehicles, regulators and security experts will find things to interest them. Sadly it does not paint a good picture of the auto industry and despite attempts to put things in a positive light the one message that comes across clearly is that national regulators need to get more closely involved to help improve cybersecurity in vehicles.

The auto manufacturers need to realise that in a connected world the lower the bar the easier it is to attack a system. Their dismissal of the complexity of launching wireless attacks is another example of the lack of serious understanding of cybersecurity at the heart of the auto industry.